Overview of the Economy

EMERGING FROM THE PANDEMIC

Total Population

309,563

Networks Northwest

Unemployment Rate

4.2%

Networks Northwest

High School Graduate or Higher

92.85%

Networks Northwest

Civilian Labor Force

147,805

Networks Northwest

REGIONAL DISRUPTIONS

The Covid-19 pandemic posed an even greater challenge than the global financial crisis that led to the Great Recession. The anxiety triggered by the uncertainty as to how and when the pandemic would end impacted leaders, employers and workers alike. The pandemic’s burdens, however, have fallen unevenly, impacting marginalized populations more severely.

The pandemic caused many to question the effectiveness of “linear thinking” with respect to problem solving and overcoming challenges, and to realize

Inclusive Revitalization:

Overcoming economic distress in a way that provides the opportunity for all residents, especially historically excluded populations to benefit and contribute.

the importance of collaboration. There was no “normal way” to handle the devastating impacts of the pandemic, and there was no clear “new normal” to embrace. The gross disparities revealed left an acute awareness that prepandemic conditions were inherently unstable and would remain so without a concerted effort to reduce stresses/stressors such as chronic poverty, lack of economic and/or educational opportunity, lack of affordable housing and/or poor access to a variety of transportation modes. This effort must begin with a clear understanding that diversity, equity and inclusion are critical components of a resilient region able to overcome challenges and minimize impacts from future disruptions.

The most significant disruptions attributable to the pandemic include:

- Job loss and unemployment due to business closures, lay-offs, resignations of workers with children due to no childcare and a need for homeschooling, and early retirement (the ”Great Resignation”). At the local government level, the non-education workforce across all Connecticut municipalities dropped by about 2,900 positions during the pandemic, giving new meaning to the phrase “lean government,” and this on top of prior municipal workforce reductions geared to balancing local budgets in response to the Great Recession. Figure 4 illustrates the percent change in employment from the prior year within SECT EDD, State of Connecticut and U.S for the period 2012Q4 – 2022Q4. Employment losses due to the pandemic are clearly indicated by the steep losses beginning 2019Q4.

- Loss of housing due to foreclosures and evictions coupled with a lack of available and/or affordable housing for residents to transition into. According to Zillow Data Research, the cost of homes in New London County increased by 38 percent since June 30, 2020 and by 110 percent since 2000. Interestingly, the primarily rural county directly to the north, Windham County, had increases of 39 percent since June 30, 2020 and 145 percent since 2000, Connecticut’s highest percentage increase. CT Fair Housing data reveal an increase from 9 percent to 35 percent in “no-cause” evictions from the six-month period just prior to the pandemic to the period between August 2021 and February 2022. Studies show that women and people of color are more likely to be evicted. Given the estimated shortage of 85,400 affordable units of housing in the state, and the sharp increases in sales prices and rents, there are precious few housing options available.

- Steep increases in the cost of living caused by increased home values (and therefore higher property taxes) and a sharp increase in cost of goods and services, particularly the cost of food in part fueled by food shortages. The hardships created by rising costs and loss of income/employment and/or housing have been further intensified by the loss of funding for nonprofits who deliver the bulk of state-sponsored social services that many rely on to survive. The Day, a daily newspaper covering a 20-town region in eastern Connecticut with a daily and Sunday readership of nearly 37,000, launched the Housing Solutions Lab, which is series of public discussions, podcasts and journalism to uplift and broaden the conversation around regional housing affordability.

- Health crisis evidenced in Covid hospitalizations and death, long-Covid complications, and non-Covid related health problems untreated/ undiagnosed.

- Disproportionate impact to tourism and hospitality industry reflected in the closure of casinos and other major area attractions and restaurants, which significantly impacted lower wage earners. By April 2020, one month into the pandemic, the leisure and hospitality employment statewide had decreased 45 percent from 157,900 to 87,000 employees. Many of the jobs remain unfilled with approximately 10,000 fewer workers at the start of 2022 than there were two years prior in the tourism and hospitality industry. This figure does not include Native American casino employment which is included under Government Employment rather than Tourism and Hospitality. Private sector employment was 92.4 percent recovered as of October 2022.

Covid-19 revealed deep inequities, the necessity of more flexible work schedules and spaces, the importance of housing and access to healthcare, and the need for a healthier work-life balance. The pandemic disrupted long-standing familiar relationships with physical spaces and traditional ways of earning an income.

Two of the most transformative consequences of the pandemic are the opportunities to learn and conduct business remotely. Remote work created opportunities for those who had been excluded traditionally from the job market such as stay-at-home parents, primary caregivers or those with disabilities. Workers without adequate or reliable transportation who could work from home had their transportation burden ameliorated as well.

Remote learning/work also revealed new challenges for different groups of people such as those with inadequate internet at home or those without a private space so as not to expose aspects of their personal life that could potentially jeopardize their career or result in discrimination. Low-wage workers (often women and minorities) have been excluded from remote work opportunities due to the nature of their jobs, e.g., nursing, retail and food, and other key service positions. Unlike most higher-wage white collar jobs, low-wage service jobs lost during the pandemic have not been fully recovered, further exacerbating Connecticut’s wealth inequality and accentuating the need to create additional pathways to wealth and fully engage any untapped workforce.

Shortages in teachers and school supplies have disproportionately impacted schools in rural areas, particularly those in high poverty areas, and/or with greater percentages of minority students (Teacher and supply shortages linger in nation’s public schools – The Washington Post).

Most of the significant problems – those critical to survival – brought to the forefront during the pandemic, whether related to access to healthcare, education, safe housing, transportation, employment, or declining mental and physical health, were proven to be far more widespread in low-income and minority communities.

Ensuring the availability of goods and services is a key component of economic resiliency which hinges on the ability to create and implement plans that advance equity through investments that directly benefit underserved populations and communities systematically denied full participation in the economy. The pandemic has provided the perfect opportunity to create truly equitable spaces within a given system (education, healthcare, employment, etc.) that accommodate and support all people in ways that allow them to equally and fully participate in the economy

IMPACTS TO TOWNS

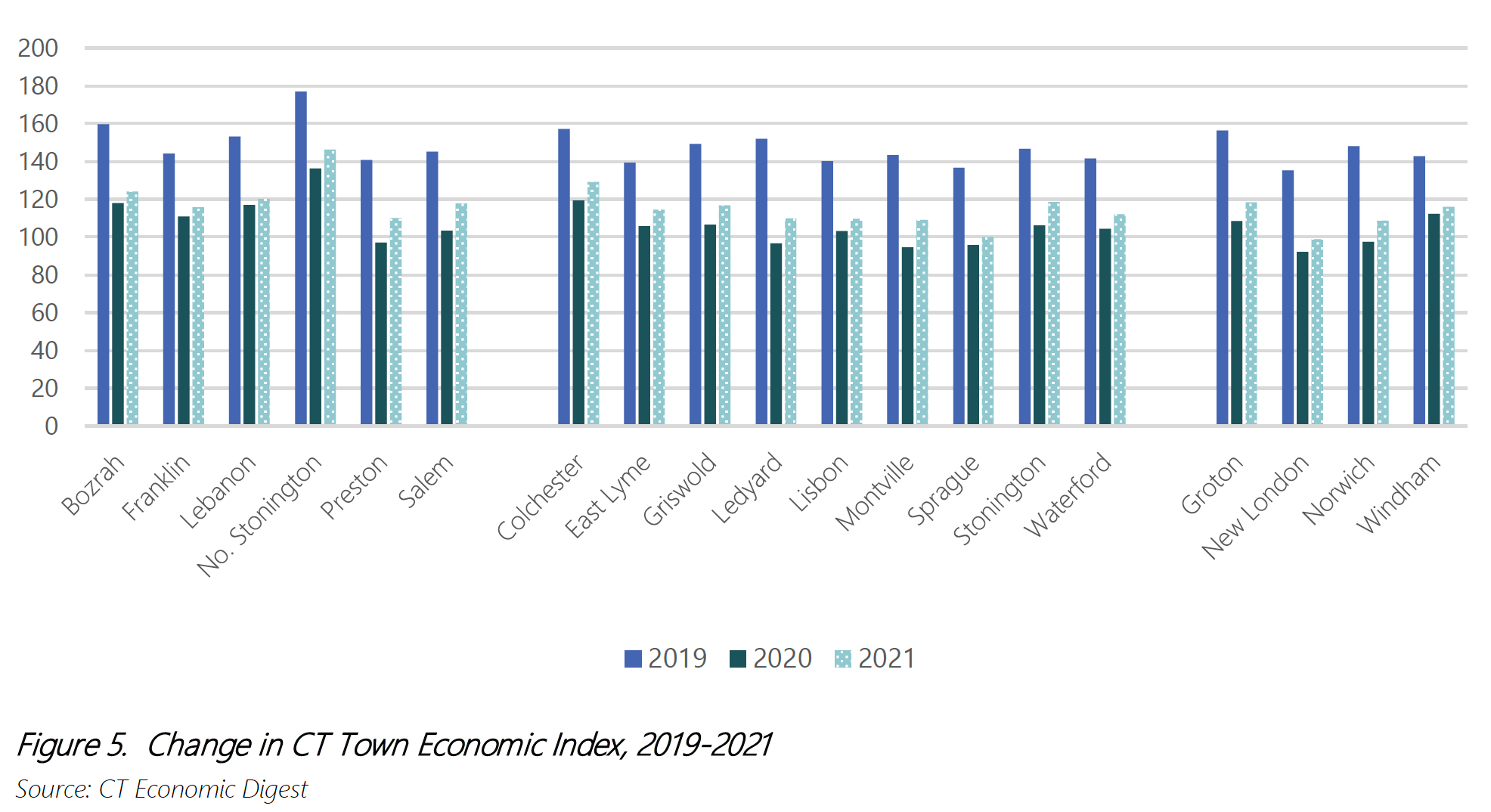

The Connecticut Town Economic Index (CTEI) measures each municipality’s overall economic health. The four economic indicators used in compiling the CTEI are 1) total covered business establishments, 2) total covered employment, 3) inflation-adjusted covered annual average wages, and 4) unemployment rate.

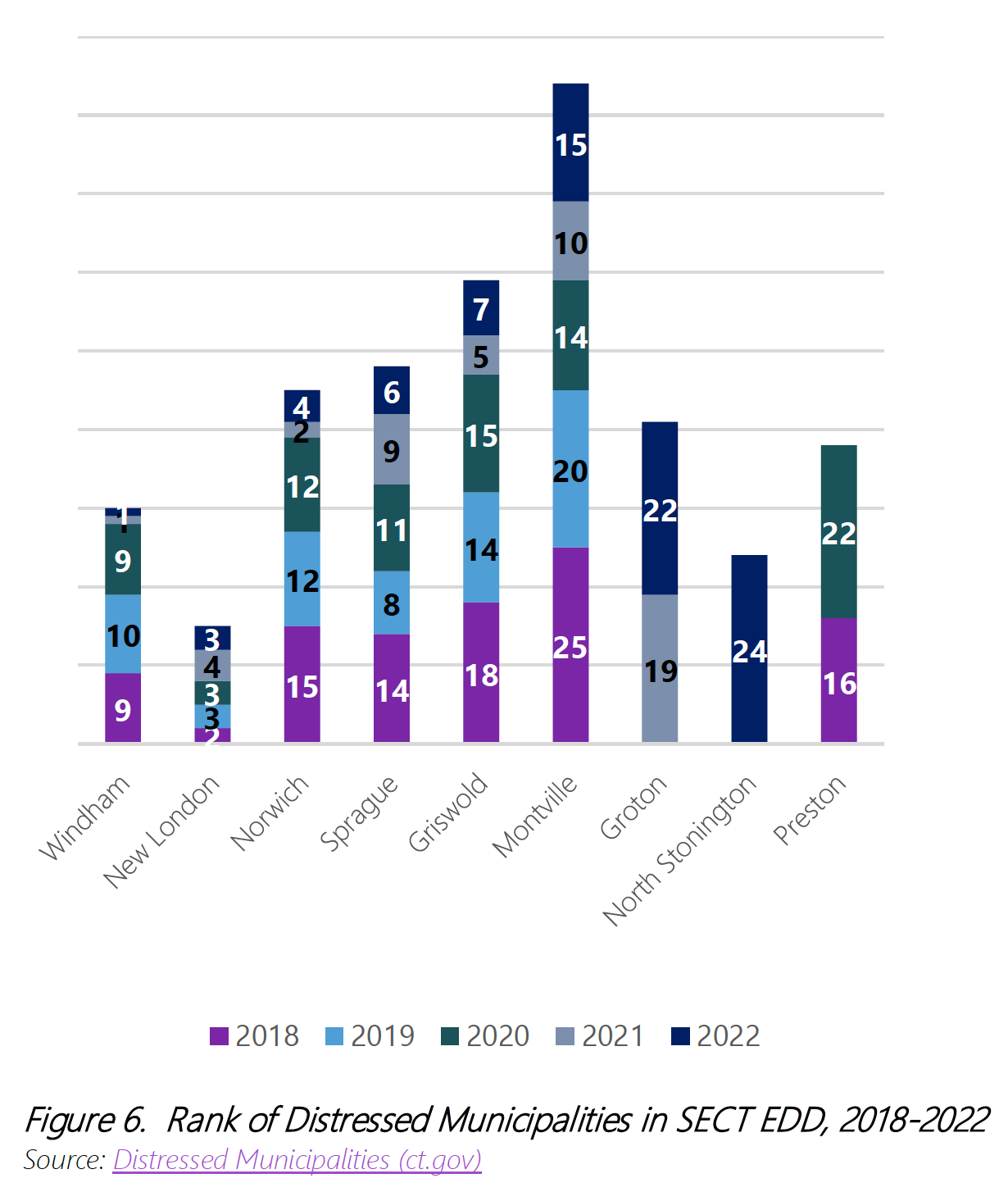

Every town in the SECT EDD saw its CTEI drop drastically between 2019 and 2020, and none has fully recovered (Figure 5). Urban towns initially dropped an average of 43 points, Suburban towns, 42 points, and Rural towns, 40 points. When compared with 2010, when employment recovery from the Great Recession began in CT, all but two municipalities showed increases in 2021. North Stonington experienced the fastest economic increase between 2010 and 2021, but still joined the Distressed Municipalities List in 2022 (Figure 6). New London was the only municipality whose CTEI fell between 2010 to 2021. Several other towns in the EDD saw a sharp rise in rank, most notably Norwich, Sprague, Griswold, Montville and Windham.

Collectively, municipalities in the region were allocated $117,806,779 in funding through the federal American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) of 2021, $1.9 trillion economic stimulus bill intended to speed up the country’s recovery from the economic and health effects of the Covid-19 pandemic and the ongoing recession. Many towns designated a portion of their funding to

support Covid mitigation efforts of Ledge Light Health District, the SCCOG Recovery Coordinator position, and art and culture initiatives through the Southeastern Connecticut Cultural Coalition, among others.

Municipalities were able to use ARPA funding for a wide variety of projects intended to provide immediate relief to businesses and residents. As reflected in the projects and programs funded, much of the funds were allocated to organizations that were best equipped to serve the immediate needs of the community while local governments developed more targeted programs to sustain ongoing recovery efforts. Towns were able to invest in much needed infrastructure and facility improvements, community connectivity improvements, sidewalks and traffic lights, park and public space revitalization projects, and open space planning. Towns were also able to provide direct assistance to struggling local businesses and households and fund housing rehabilitation programs.

IMPACTS TO LOCAL BUSINESSES

Pandemic-related issues and impacts for businesses and industries included:

- Labor shortages

- Supply chain disruptions

- Business closures

- Lack of access to emergency funding

- Adjustments to operating hours

- Expansion into outdoor dining, take-out/delivery services

On a large scale, the pandemic underscored the need for greater investment in information technology infrastructure and research institutions. Locally, the ability to assist local businesses was crucial. There have been unparalleled investments at the national level for businesses, and SECT was able to capture some of that investment. Pandemic relief funds for businesses under the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) resulted in 4,770 loans, which helped to retain nearly 50,000 workers in the region (Table 3)

Table 3. Summary of PPP Loans in New London and Windham Counties

SOURCE: Connecticut PPP Loans

Norwich Public Utilities (NPU) and Three Rivers Community College (TRCC) are leading examples of how regional organizations in differing industry sectors were impacted by and responded to the pandemic. Details of their innovative approaches are provided in Appendix J.

The need for greater collaboration was central to CEDS 2017. The pandemic put the very concept of collaboration to the test. Through the implementation of CEDS 2023, seCTer aims to strengthen the collaborations formed during the pandemic and facilitate the creation of new ones. The pandemic exposed the vital connection between diversity, equity and inclusion, and resiliency. It exposed the instability of the economy due in part to the number of people excluded from participating in or contributing to it. The disruption has once again brought attention to the need to refocus attention to the local level; identify the barriers to building capacity and systems needed to enhance regional resiliency; engage in collaborative efforts; activate the untapped members of the economy; and embrace the diversity found in the region. The path to a more resilient region must begin with a shift in thinking and behavior at the local level and a willingness to align behind a shared vision for the region, rather than advancing (at times) conflicting local priorities. Leadership must be aligned and actions must be sufficiently transformative to gain visibility and attract capital to move the whole region ahead.

CEDS 2017 was noted for its flexibility, and CEDS 2023 too is an adaptable document. The continued engagement of the CEDS Strategy Committee, SCCOG and the business community will help ensure that conversations about the direction and priorities identified in CEDS 2023 remain relevant and timely. With pandemic recovery still shifting the tides of the SECT EDD economy, CEDS 2023 aims be a stabilizing force.